DMARD monitoring during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Authors:

-

Posted:

- Categories:

In this blog, Andrew Brown describes some of our recent work, now published in the British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, investigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on DMARD safety monitoring across 24.2 million patients’ records in England.

Why did we do this research?

We know that the COVID-19 pandemic had a huge impact on healthcare, with previous research showing that many routine tasks were impacted. We wanted to look at the impact on disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD) safety monitoring, and see if any particular medications, monitoring tests, or patient groups had been particularly affected.

Background on DMARD monitoring

Many DMARDs have a small dose range between beneficial and harmful effects, so without careful control they can cause potentially fatal toxicity. To reduce this risk, DMARDs are typically initiated by a specialist clinician in secondary care. Once patients have been stabilised on treatment, they can be transferred to primary care under a shared care protocol, which specifies long-term safety monitoring recommendations for general practitioners (GPs) to oversee. Below are examples of 3 DMARDs, in each case showing their licensed indications typically seen in primary care, and their minimum long-term monitoring requirements.

| Drug Name | Indications | Long-term Monitoring* |

|---|---|---|

| Azathioprine | Crohn’s disease, severe eczema, myasthenia gravis. | Every 12 weeks: FBC, U&Es, LFT |

| Leflunomide | Rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis. | Every 12 weeks: FBC, U&Es, LFT, BP |

| Methotrexate | Crohn’s disease, severe psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis. | Every 12 weeks: FBC, U&Es, LFT |

*FBC: Full Blood Count, U&Es: Urea & Electrolytes, LFT: Liver Function Tests, BP: Blood Pressure.

During the COVID-19 pandemic some national recommendations were made about how to manage DMARD monitoring. These recommendations aimed to balance the importance of safety monitoring whilst reducing the spread of COVID-19 by minimising contact with healthcare professionals.

-

The British Medical Association and Royal College of GPs issued guidance suggesting clinicians consider DMARD monitoring a high priority task.

-

The NHS Specialist Pharmacy Service and British Society of Rheumatology suggested that monitoring intervals for DMARDs could be considered for extension.

How did we do this research?

OpenSAFELY

With the approval of NHS England, we used the OpenSAFELY platform to look at 24.2 million patient records and identified patients receiving prescriptions for azathioprine, leflunomide, and methotrexate between November 2019 and July 2022.

How did we decide which DMARDs to include?

We picked these drugs as examples of commonly prescribed DMARDs which are consistently managed in similar ways under shared care protocols.

How did we decide which patients to include?

We only wanted to include patients taking long-term DMARDs (where monitoring requirements were more likely to be stable), so we defined our study population as patients recorded with at least 2 DMARD prescriptions (one issued within 3 months before the search date, and the other between 3 and 6 months before the search date).

How did we define missed monitoring?

We checked whether these patients had the relevant monitoring tests coded in their medical records within 3 months before the search date. If they did not, then this was recorded as a missed monitoring event.

What did we find?

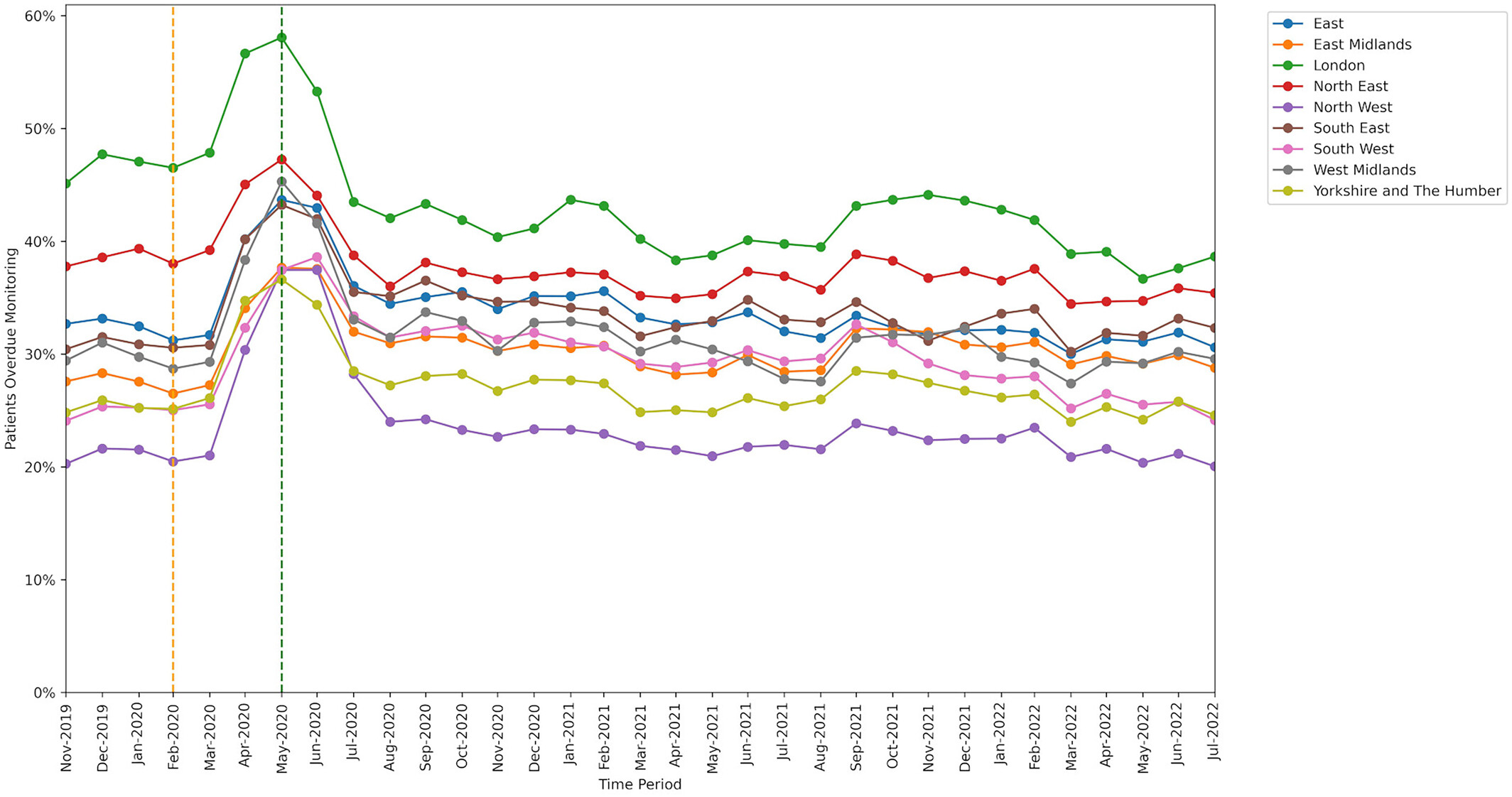

There was an increase in the rate of missed monitoring (+12.4 percentage points) across the study population when lockdown measures were implemented in March 2020, however this rapidly recovered between June - August 2020, and by the last month of our study (July 2022) had returned close to baseline rates.

Medication type

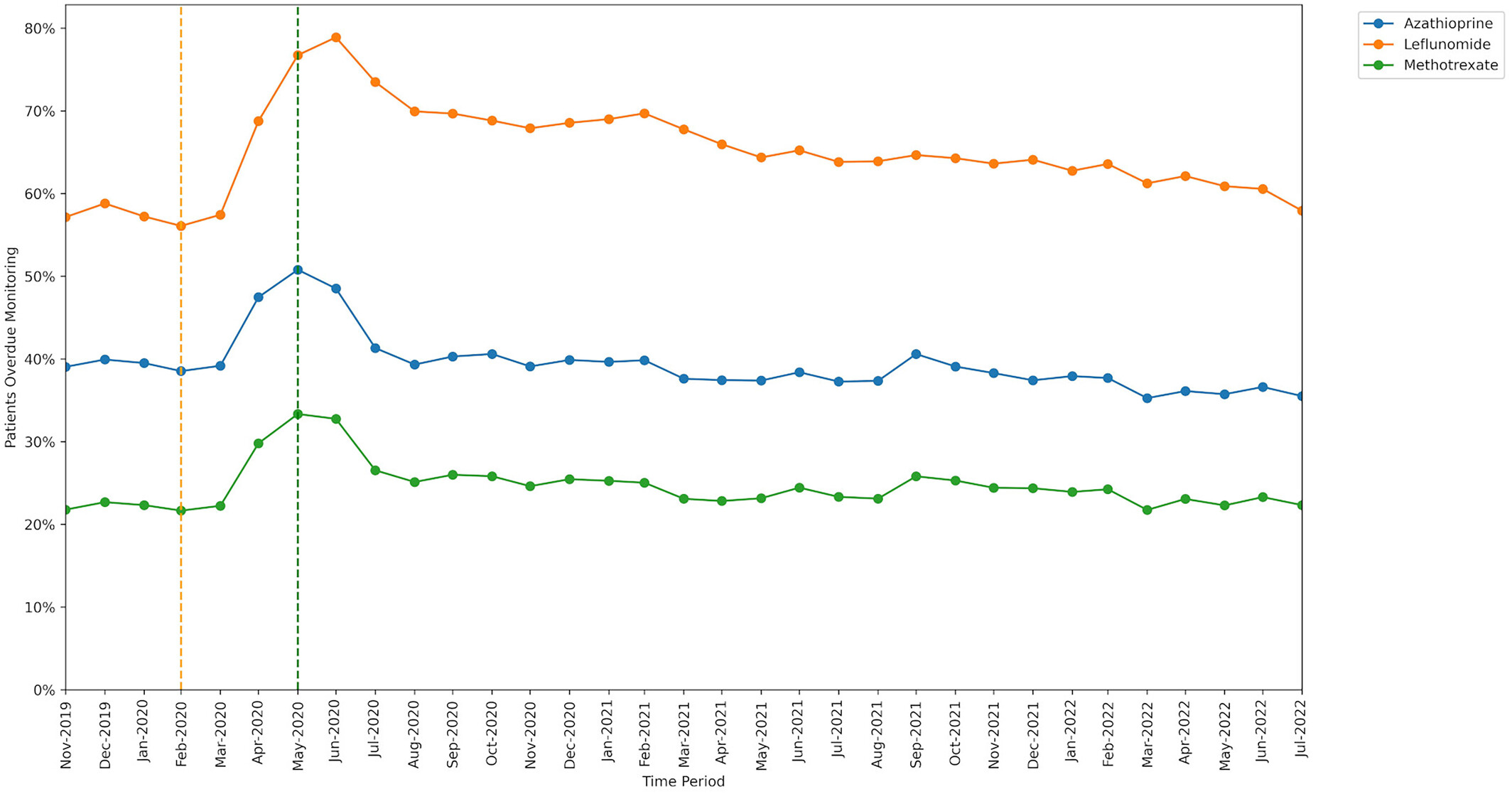

The percentage of patients identified as missing monitoring was greatest for leflunomide and lowest for methotrexate. The increase in missed monitoring rates between the baseline and lockdown period was similar for methotrexate and azathioprine, but a noticeably greater increase was seen for leflunomide.

Monitoring type

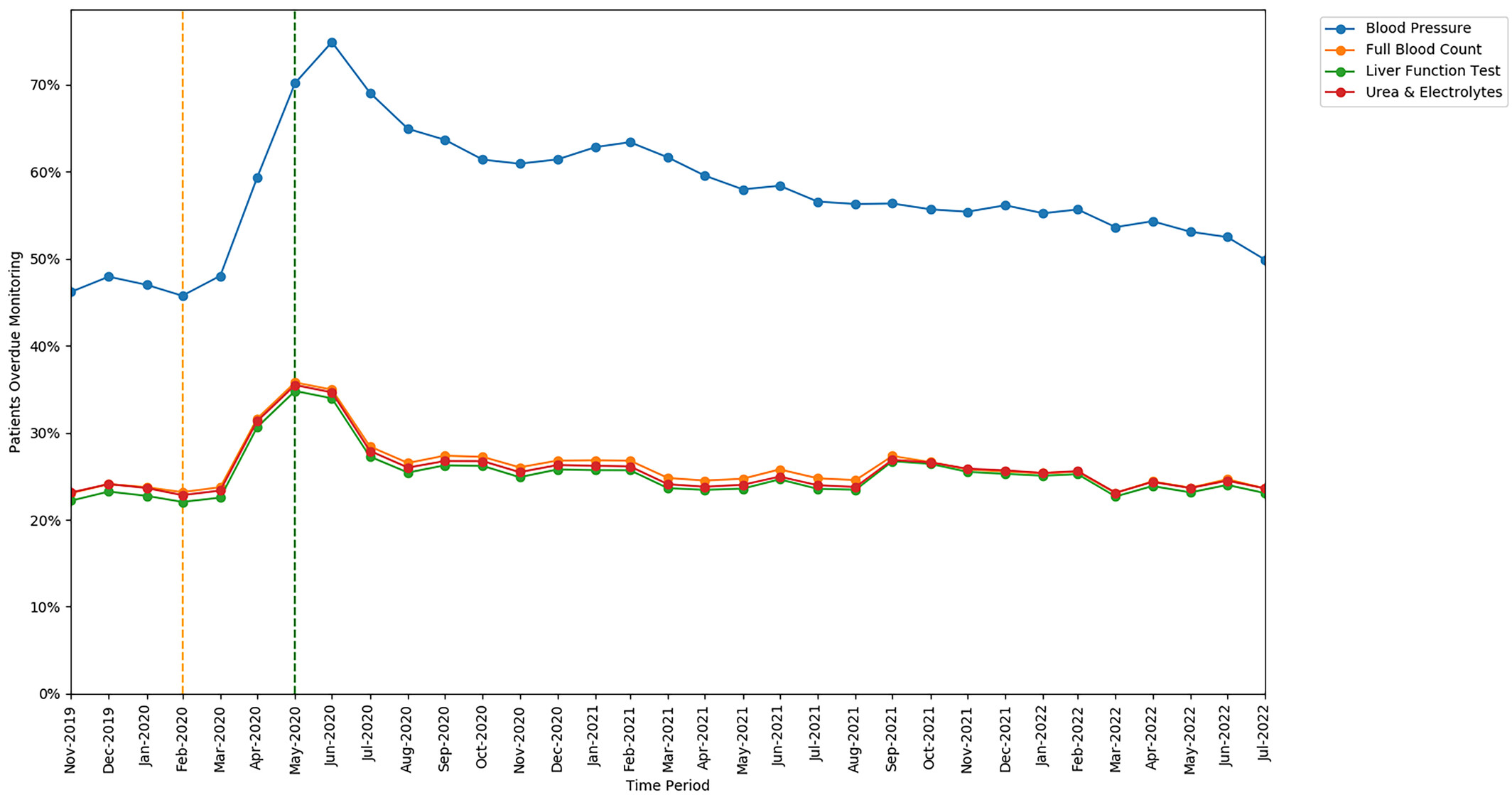

The rates of missed monitoring were similar for FBC, LFT, and U&Es, but were substantially higher for BP tests (a unique requirement for leflunomide). The increase in missed monitoring rates between the baseline and lockdown period was also similar for FBC, LFT, and U&Es, but a greater increase was seen in the rate of missed BP monitoring.

Patient groups

We broke down our results into several demographic and clinical groups, finding consistent differences in overall missed monitoring rates between several groups throughout the study, below are a few of the examples we found particularly interesting.

Age

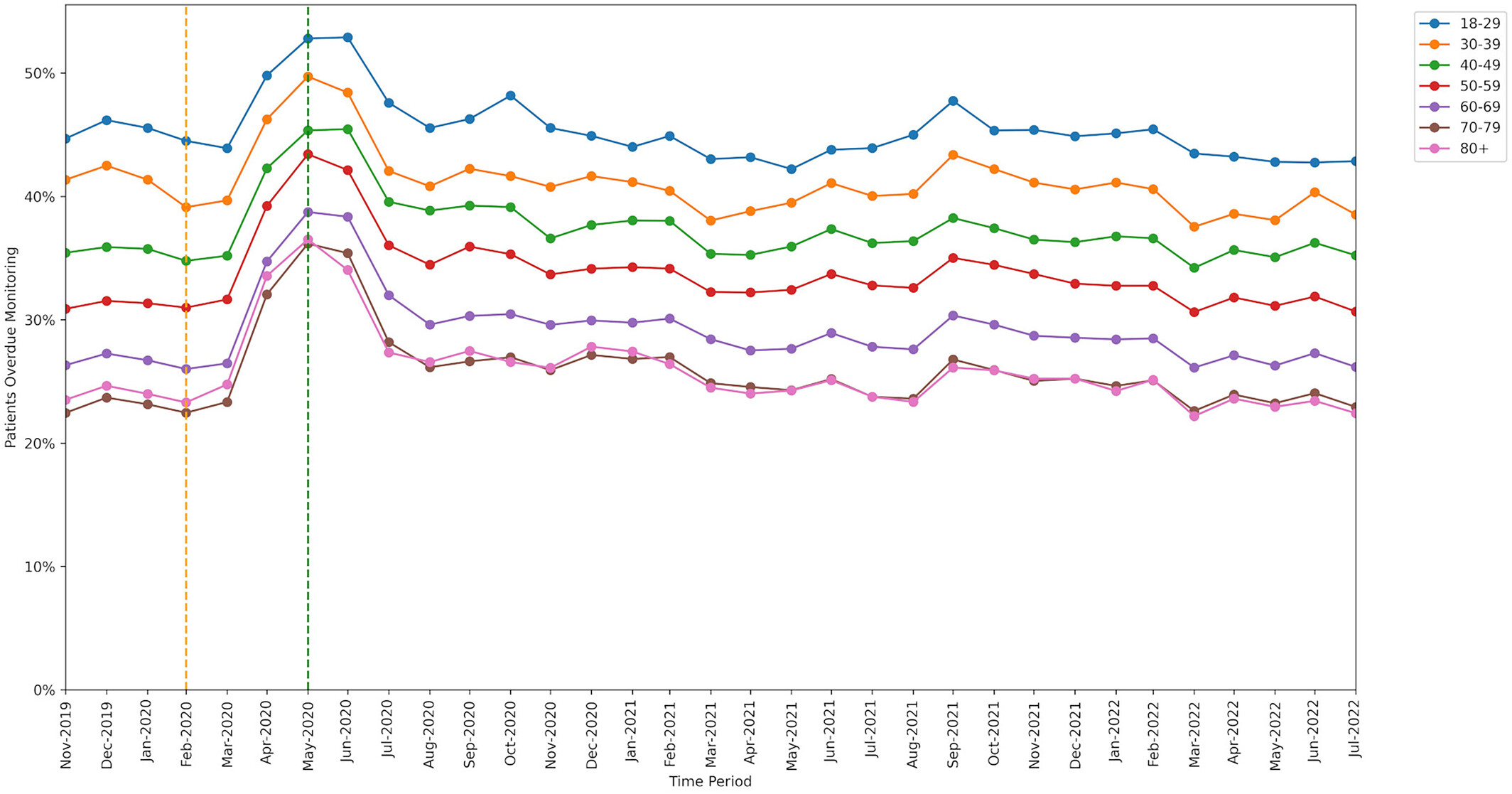

Younger patients missed monitoring more often than older patients.

Ethnicity

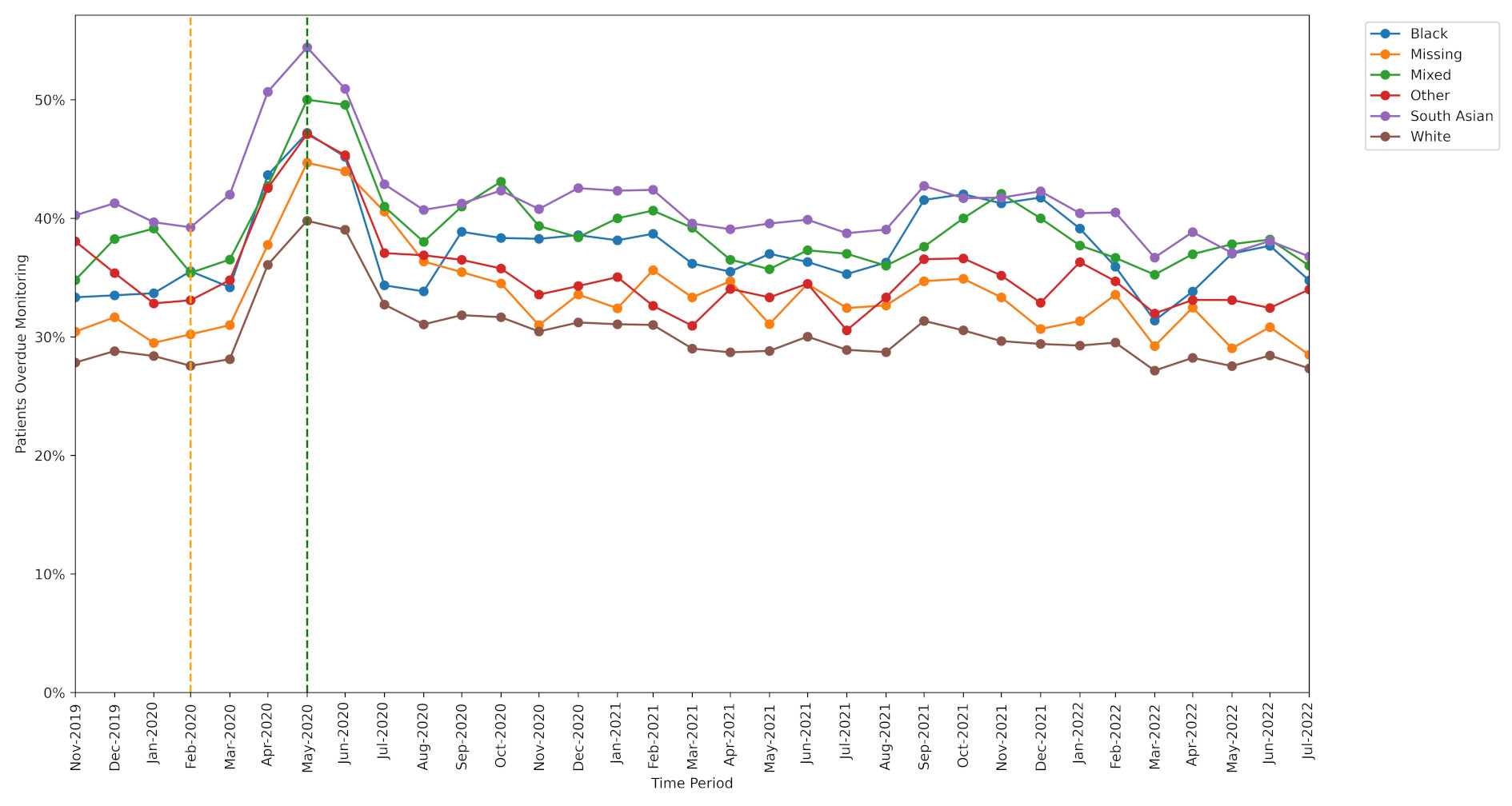

Patients belonging to an ethnic minority group missed monitoring more often than White patients.

Region

The range of missed monitoring rates when broken down by region was wider than for any other breakdown type we used in our study, with ‘London’ having the highest missed monitoring rate and ‘North West’ having the lowest.

Our paper provides more detailed results on DMARD monitoring including practice level variation and breakdowns by sex, Index of Multiple Deprivation, rural-urban categorisation, care home residents, patients who were housebound, patients with learning difficulties, patients with serious mental illness, and patients with dementia.

Implications and future opportunities

This research highlights that DMARD monitoring is often not adhered to, with patients being overdue for monitoring at an average rate of 31.1%. However, large geographic variability suggests that some areas have implemented more effective strategies, offering opportunities for sharing best practice. The differences seen in monitoring rates between medications, tests, and patient groups highlight opportunities to tackle inequalities in the provision or uptake of monitoring services. Further research could evaluate the causes of the differences identified between groups.

These findings also raise questions about whether current monitoring requirements are appropriate for all patients, as well as the clinical impact of missed monitoring. An audit assessing the effect of delayed methotrexate monitoring found no evidence of excess harm. However, it’s crucial to consider the potential for confounding by patient-specific factors related to clinical risk, which influence the likelihood of monitoring occurring, e.g. patients at lower risk may be less motivated to attend monitoring.